Item number: 60201

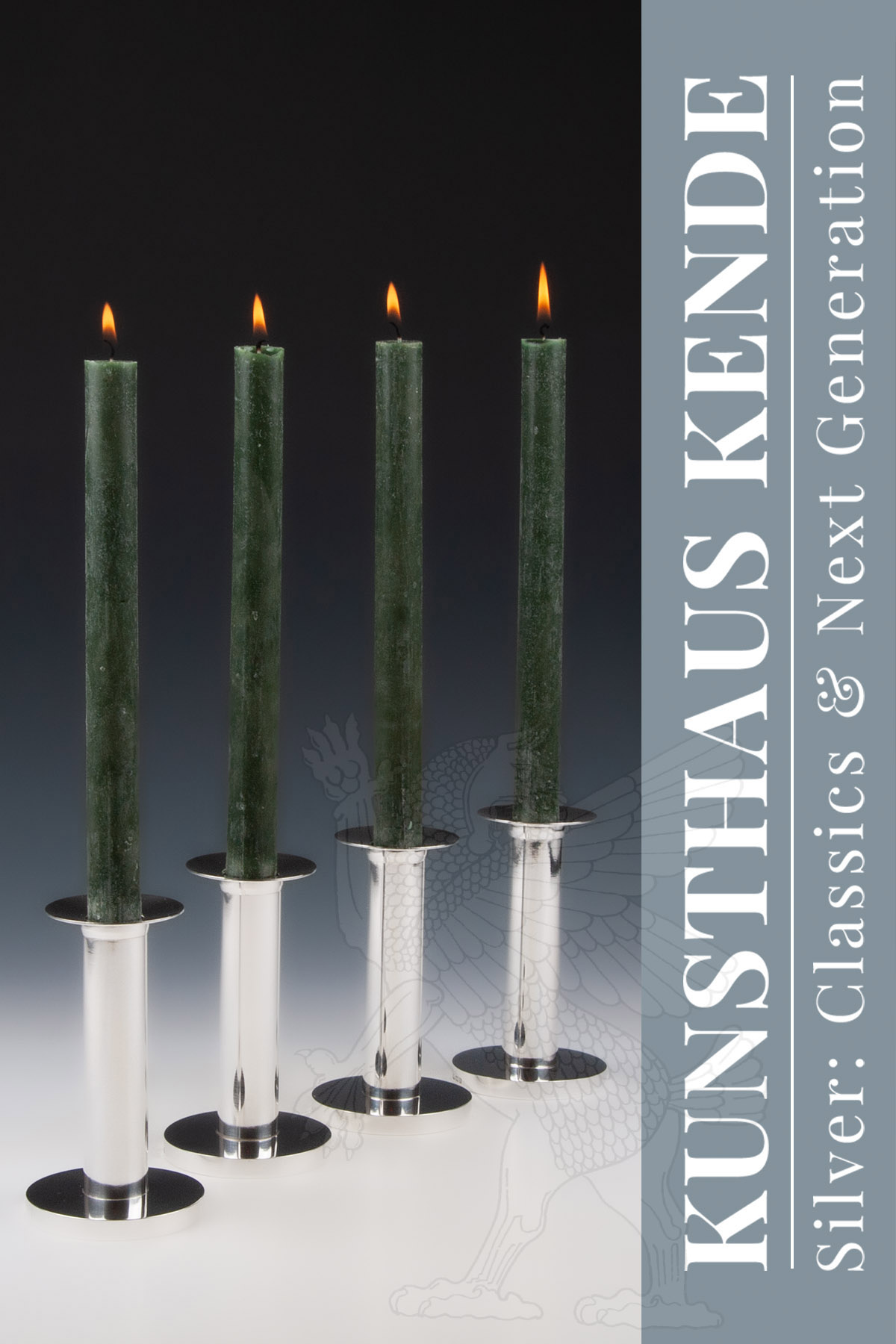

A very rare set of four sterling silver candlesticks,

Würzburg/Germany 1969 by Andreas Moritz

Standing on a flat base, the elongated, cylindrical stem is profiled at the top towards the spout which is removable for the purpose of cleaning.

A very rare set of four candlesticks in sterling silver, excellently crafted and of a modern elegance.

12.7 cm / 5″ tall, 7.2 cm / 2.83″ diameter (base)

Candlestick 1: 210.9 g / 6.78 oz

Candlestick 2: 210.7 g / 6.77 oz

Candlestick 3: 210.7 g / 6.77 oz

Candlestick 4: 211.2 g / 6.79 oz (none of them weighted)

As one of Germany’s key figures in the post-1945 period, Andreas Moritz was a silversmith, designer and teacher who played a decisive role in post-war silver craftsmanship and its development. His teaching at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste (Academy of Fine Arts) in Nuremberg had a fundamental influence on subsequent generations of aspiring silversmiths. In addition to the outstanding quality of his silverware and table silver, his works also have an almost sculptural character that testifies to a keen sculptural sense for balanced, pondered and tranquil forms. With his work, Andreas Moritz also stands as a mediator at the threshold between the traditions of the Bauhaus and post-war modernism. Significantly, throughout his life, his circle of customers consisted mainly of artists, intellectuals and the nobility. For example, his records show that Karl Schmidt-Rottluff purchased six wine goblets in sterling silver from him in 1971/72.

His estate is now owned by the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg. The four other candlesticks of this set, along with other works by the master, are also in the possession of the Museum of Modern Art, New York (see here).

To list all of his awards, prizes and museum exhibitions would go beyond the scope of our website, so please refer to the literature for more information on this topic.

The silversmith Andreas Moritz (Halle a. d. Saale 1901 – Würzburg 1983)

Born the son of a lithographer, Andreas Moritz was taught to place great importance on handwriting and drawing as a child. At the age of 16, Andreas Moritz finished school and began an apprenticeship as a toolmaker, where he learned the basics of manual metalworking. He soon dropped out of his subsequent studies at the Karlsruhe State Technical College and spent about two years travelling. By chance, during a stay in Halle a. d. Saale, he became aware of the local technical and craft school. A group of progressive craftsmen around Paul Thiersch was in the process of splitting off from the teaching institution and moving to Burg Giebichenstein to pursue new artistic approaches there.

At that time, the Bauhaus and the Burg Giebichenstein workshop were among the first educational institutions in Germany to focus their teaching on modern craftsmanship. In the case of silverware and creations in nickel silver and non-ferrous metals, this meant in particular a focus on the new bourgeoisie and its demands for contemporary, modern, ornament-free design while maintaining practicality. Andreas Moritz joined the Burg Giebichenstein teaching workshop, where he remained for a relatively short period before setting out on his travels once again. Artistic influences from sculpture, resulting from encounters with Bernhard Hoetger and Heinrich Vogeler, were to have a lifelong impact on his work. In 1922, Andreas Moritz returned to Halle to continue his training at Burg Giebichenstein. However, in 1924 he was poached by the Kunstakademie Kassel (Kassel Art Academy), where he was to take over the teaching of art and craft teachers in the metalworking class. Andreas Moritz did not stay here long either; his desire to continue his artistic training led him to Berlin. Andreas Moritz completed his studies in 1932 with a master student diploma at the Vereinigte Staatsschule für freie und angewandte Kunst (United State School for Fine and Applied Arts) in Berlin-Charlottenburg, directed by Bruno Paul. There he studied sculpting with Ludwig Gies and metalworking with Waldemar Raemisch, among others. In 1933, he was expelled from the university by Bruno Paul’s successor, Max Kutschmann, because of his non-conformist attitude towards the National Socialist regime. Although Andreas Moritz retained a great affinity for sculpture, his decision to work as a silversmith was certainly also based on the fact that at that time, the main commissions were for memorials, monuments and other sculptural works for public spaces – works that he could not reconcile with the new authorities.

Although he continued to work as a sculptor, only a few busts in stone and bronze works have survived from his sculptural œuvre; most of it has been preserved only through contemporary photographs. After his expulsion, Waldemar Raemisch offered him the opportunity to use the university workshop until he had his own studio. Despite his expulsion from the Vereinigte Staatsschule and his contacts with the Bauhaus (some of his silver works exhibited at the Bauhaus were confiscated during a raid), the National Socialist rulers could not help but recognise his high level of craftsmanship and artistic skill. He was therefore offered the position of Reichssilberschmied (a silversmith being responsible for carrying out state commissions), which Moritz declined. His continued clear opposition to the regime brought him into increasing difficulty, so that from 1934 to 1939 he taught at the Central School of Arts & Crafts in London. The strong tradition of silversmithing in England and the silver of the 18th century left a lasting impression on him, which was also reflected in his later teapots and coffee pots. The outbreak of war in 1939 forced him to leave England and he settled in Berlin as a freelance silversmith. In 1941, Andreas Moritz was drafted into the army, in 1942, his workshop was completely destroyed by a bomb. In 1944, he was granted marriage leave, during which he married his wife Berta Moritz-Siebeck in Hinterzarten in the Black Forest. Towards the end of the Second World War, he was taken prisoner of war, from which he was released in 1947.

This was followed by a move to Hinterzarten, where he opened his workshop in 1948. In 1950, he exhibited his silverware for the first time in Schwäbisch-Gmünd. The attention he attracted there as a silversmith with his exceptionally elegant silverware led to his appointment as a professor at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste (Academy of Fine Arts) in Nuremberg in 1952. After the teaching building of the Nuremberg Academy, which had been completely destroyed by bombing, was rebuilt, he set up a modern teaching workshop for silversmiths there. In 1968, he moved to Würzburg, where he remained until his death.

As a person who was not easy to get along with throughout his life but always true to his principles, his silverware craftsmanship reveals his supreme artistic sense of form, which was influenced by sculpture, and his uncompromising precision, which he acquired in his younger years as a tool mechanic. Andreas Moritz did not see his work as mere commodities that he produced to earn a living, but as the materialised creative work of his intellectual and artistic genius. His artistic self-confidence as a silversmith was also reflected in the fact that he rarely sold his works, but instead usually made copies of them for sale. In addition to teapots, drinking bowls (often reminiscent of works from Greek antiquity), cups and bowls, Andreas Moritz is also known for his ecclesiastical silverware. Among the liturgical objects he created, the seven-armed candelabra in Würzburg Cathedral is particularly noteworthy. Andreas Moritz also forged silver flatware and cutlery (including steel blades of the knives) which, as independent cutlery designs of the post-war period, follow on from the important cutlery designs of Emil Lettré and Wilhelm Wagenfeld.

Of the students taught by Andreas Moritz, the silversmith Wilfried Moll is particularly well known to the general public. Wilfried Moll, born in Hamburg in 1940, was a master student of Moritz from 1962 to 1965 and graduated with a diploma. Even after Moll’s training period, the two silversmiths remained close friends, which is also reflected in the silverware of both artists. The works of both silversmiths are characterised by geometric rigour in their design, which is based on spheres, triangle and square. In some cases the work of both is so closely interwoven that it is not always possible to clearly attribute the authorship of a design to one of the two designers – a detail that also occurs in art history in the silver works of the Wiener Werkstätte, where individual works can be attributed to both Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser.