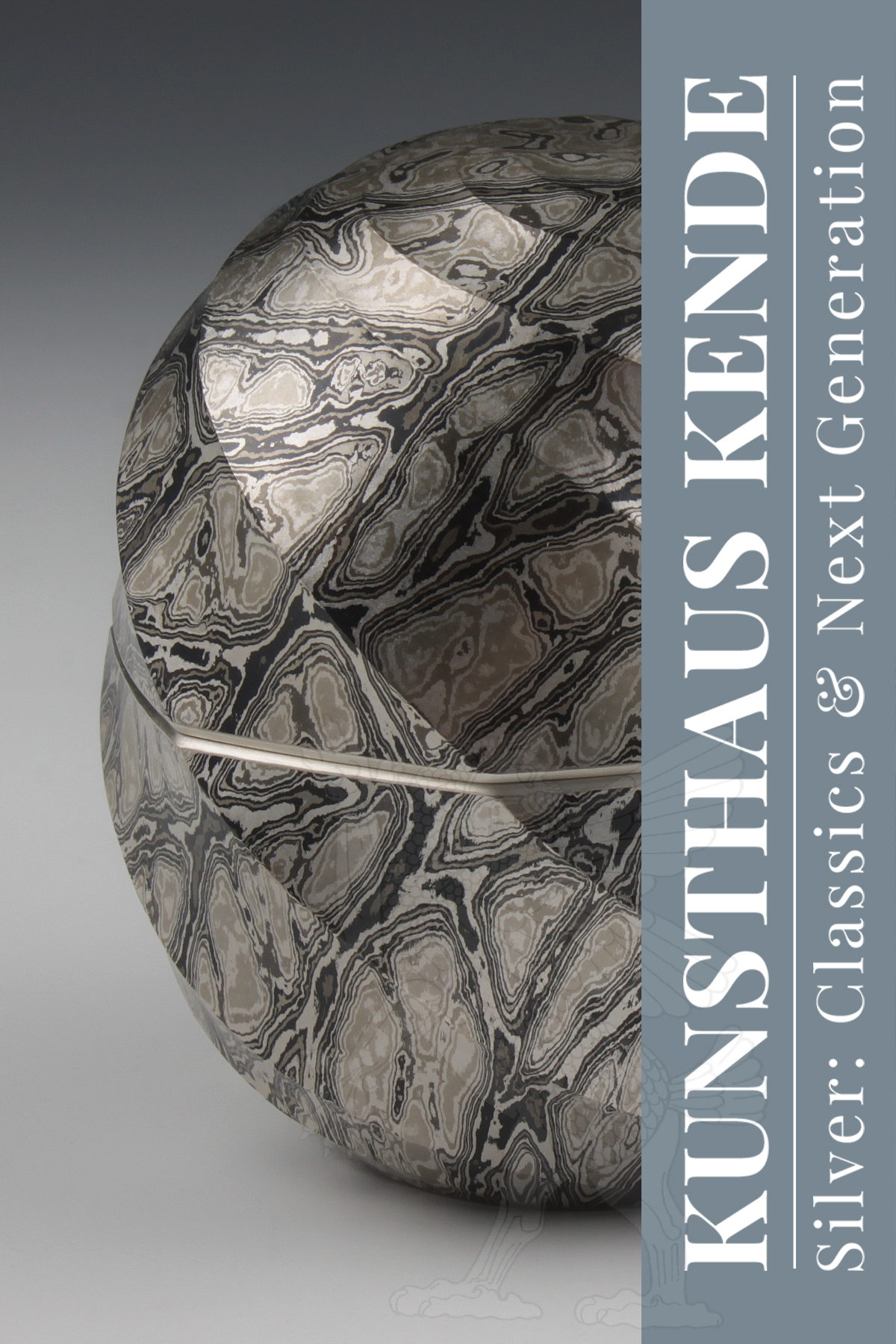

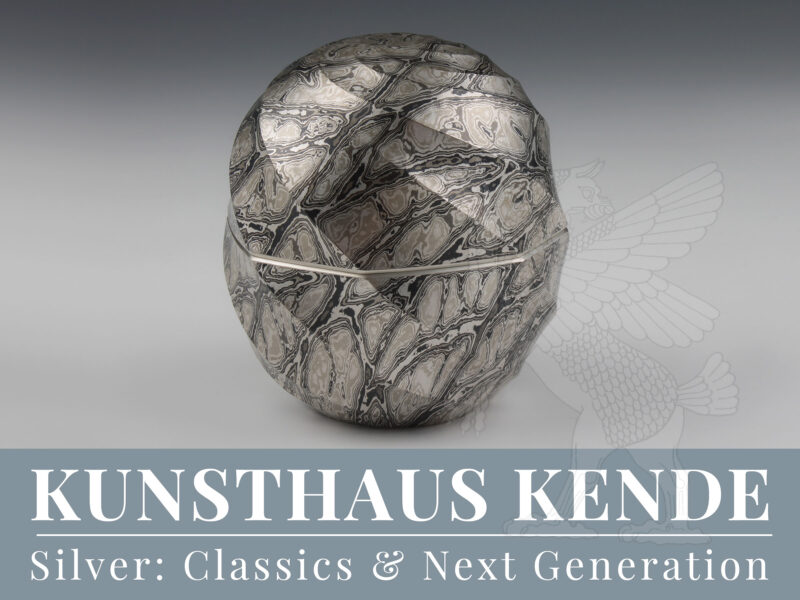

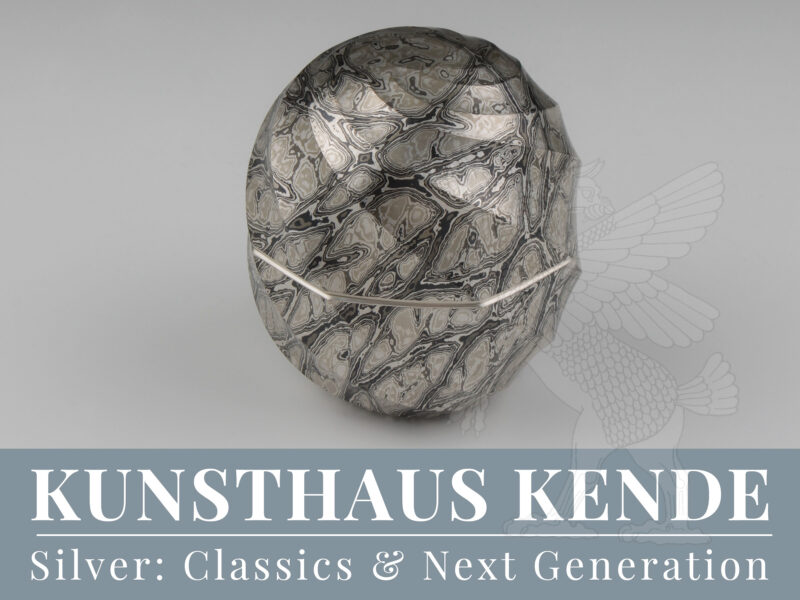

Item number: 60121

A silver and Mokume-gane tea caddy,

Silver, Copper, Shakudo, Shibuichi, Kuromido,

Okayama 2023 by Ryuhei Sako

The circular body is decorated with evenly spaced spiral ridges. The inside is made of solid silver as is the bottom. The lid is removable and designed so that it can only be placed in one position to maintain the pattern. The object comes in a storage box signed by the artist.

Masterfully shaped and elegant tea caddy by one of Japan’s most important contemporary artists for objects in Mokume-gane.

In addition to the extraordinarily difficult and intricate production method of the source material alone, this object, as well as the other tea caddy and the Mizusashi currently on offer, must be particularly emphasised for the special skill with which the extremely precise spiral shape was executed.

8.2 cm / 3.22“ tall, 7.5 cm / 2.95“ diameter (widest part)

In addition to fine silver (999 silver), pure copper and the traditional metal alloys shakudo, kuromido and shibuichi were used in the manufacture of this tea caddy. Shakudo is an alloy of copper with an addition of 1 to 5 % gold. Kuromido is unrefined copper in its state of discovery, which may contain traces of antimony or iron, among other metals. Copper was processed in this form in Japan for centuries because the technical possibilities for chemical purification of the metal were not available. Shibuichi is an alloy of silver and copper. The outer surface is coloured using a traditional Japanese patination technique called Niiro. This gives the different metal alloys an additional vividness by increasing the contrast. In this process, the copper turns a reddish brown, Kuromido gets a dark black. Shakudo, which is also black, takes on a blue tinge and Shibuichi a matt grey tone, the colour of which can vary depending on the mixing ratio of silver to copper. The colours of gold and silver remain unchanged.

The historical development of Mokume-gane

Mokume-gane is a traditional Japanese forging technique that developed in the early Edo period (beginning of the 17th century). The very elaborate technique developed in Japan as a result of the limited supply of precious metals. Mokume-gane was initially used as a decorative element on samurai swords, especially in the manufacture of finger protector, the so-called tsubas. With the extinction of the samurai and the accompanying pacification of the population through disarmament, the blacksmiths were forced to find new outlets. As a result, the knowledge of this technology was forgotten.

The manufacture of Mokume-gane

Mokume-gane literally means “wood-grain metal”, which refers to the appearance of the finished forged metal reminiscent of wood grain. Mokume-gane, along with Itame-gane and Masame-gane, belongs to the layering techniques, roughly comparable to Damascus steel. In this technique, a large number of different, thin layers of metal are laid on top of each other and joined together by multiple annealing and subsequent hammering to form a block. Itame-gane has a ring-shaped appearance, while in Masame-gane the metals form a parallel pattern. In Mokume-gane, the surface of the finished layered block is cracked by engraving and drilling. The block is then hammered and annealed regularly to form a thin plate. The previously made engravings and drill holes are pulled apart until they are at the same level as the surrounding surface. The production technique is highly complex and is only mastered by very few specialists. One of the main difficulties is to achieve the exact temperature and the right duration for heating the layer block, as the metals have to be heated to just before their melting point in order to bond with each other. The diverging melting points of the metals used present the greatest challenge in this operation. The subsequent hammering of the layer block also requires many years of experience as well as great strength, a high degree of craftsmanship and feeling for the material in order to prevent the metal, which is becoming thinner and thinner, from cracking. The finished metal plate can then be further processed to form the object.

The artist silversmith Ryuhei Sako

Ryuhei Sako was born 1976 in Okayama, capital of the Okayama administration, in southern Japan. As a student, a special exhibition presenting the work of Norio Tamagawa aroused his interest in the technique of mokume-gane. It was not until his third year at university that the artist began to specialise in metalwork. In 1999, he graduated from the Faculty of Art of Hiroshima City University with a Bachelor’s degree, followed by studies at the Graduate School of Art of Hiroshima City University. He completed his studies with a Master’s degree in 2002 and established his workshop in Tamano City, Okayama Prefecture in 2003. In 2005, he moved his workshop to Okayama City, where he is still based. Ryuhei Sako has been a member of the Japan Art Crafts Association since 2004.

During his studies, the artist’s desire to specialise in the highly demanding technique of Mokume-gane was consolidated. As there were no suitable teachers for this at the time, Ryuhei Sako had to resort to in part historical writings and reference books. After opening his own workshop in 2003, the artist began the actual process of learning the technique, which was to take over ten years.

Today, Ryuhei Sako is one of the few artist silversmiths worldwide who have achieved an outstanding mastery in the field of Mokume-gane. In his objects, he combines centuries-old traditions with the 21st century in both technical and artistic terms. His formal language is based on traditional Japanese vessel forms and reinterprets them. He has also decisively developed the mokume-gane technique through his research in this field. As a self-taught artist, Ryuhei Sako has spent years experimenting with the colour nuances that result from the different mixing ratios of the alloy metals used in the production of shakudo and shibuichi.

In view of his outstanding artistic achievement, it is hardly surprising that his work has been honoured by several awards. His artworks form part of the inventory of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, Oxford as well as of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.